B2B Market Segmentation: Expert Insights and Case Studies

By Adam Fischer • February 11, 2026

How to Think About B2B Segmentation

In this article, we’ll go deep into the mechanics of B2B segmentation, from analyzing macro market conditions to breaking markets into meaningful structural segments, and then laddering down into precise customer definitions and ICP development. I’ll share practical examples, frameworks, and case studies to make the thinking and process as concrete as possible.

The goal is to give you a structured way to think through segmentation so you have something actionable to use across marketing, sales, and your entire business.

Real B2B segmentation is very deep work.

It requires System 2 thinking: slow, analytical, deliberate reasoning. The kind of thinking where you challenge assumptions, hone definitions, revisit boundaries, and pressure-test your logic against real data and real customer conversations.

You'll need to ask questions like:

- How is this market structurally evolving over the next 3–5 years?

- Where is growth concentrating? Where is margin compressing? Where is capital flowing? Segmentation that ignores structural shifts quickly becomes outdated.

- How do market segments differ in size, growth rate, and profitability potential?

- Do these groups operate under different cost structures, ownership models, channel strategies, or growth pressures? Segmentation should illuminate differential economic attractiveness.

- How is the competitive structure different across segments?

- Assess competitor presence, intensity of rivalry, and basis of competition. Who is winning and why? Are market segments dominated by one large competitor, or is share fragmented?

- What distinct customer groups exhibit meaningfully different needs, motivations, and use contexts?

- Customer segments should reflect real differences in problem structure and value sought.

- Which customers feel the pain most acutely and most frequently?

- Not just who “could” use the solution, rather who experiences the problem in a way that creates urgency. Who responds best to your positioning and value propositions?

- How do buying criteria and decision processes vary across segments?

- Differences in evaluation criteria, risk tolerance, and decision roles may define viable segments.

- What event or trigger typically initiates the buying process? Regulatory change? New funding? Leadership turnover? Expansion? Segments behave differently when their buying triggers differ.

- Which segments are strategically vulnerable or underserved?

- Look for misalignment between customer needs and current market offerings.

- Where do the firm’s competencies and assets provide a defensible advantage?

- Segmentation should connect to where the firm can compete effectively.

- What must be true for this to be a high-probability, high-value customer?

- Define the non-negotiables. Revenue range. Tech stack. Organizational maturity. Operational complexity. Strong segmentation excludes.

- If we narrowed this segment further, would performance improve?

- This is the pressure-test question. Strong segmentation often becomes more powerful as it becomes more specific.

Good segmentation is iterative. You define a segment, test it against reality, refine it, and sharpen it again. You may start broad and realize the real opportunity sits inside a narrower structural slice. Or you may discover that two segments you thought were distinct actually share the same buying logic.

This is normal.

B2B segmentation is not a static document. It evolves as markets evolve. It improves as your understanding improves. It strengthens as you test messaging, analyze deal velocity, and study which customers actually convert, expand, and renew.

That’s why the process matters even more than the output.

Here's a broad view of the process starting at the market level and ending with a profile of key decision makers:

- Define the Market: Start by defining and outlining the boundaries of your market, the macro forces shaping demand, competition, and structural shifts. This will yield sub-markets from you to choose from and prioritize.

- Build Customer Segments: Create distinct customer groups within your chosen market or sub-market based on meaningful structural differences such as economics, ownership model, growth trajectory, operating model, and buying dynamics.

- Choose the Target Segment: Select the customer segment you will prioritize based on strategic fit, urgency, economic power, and probability of winning.

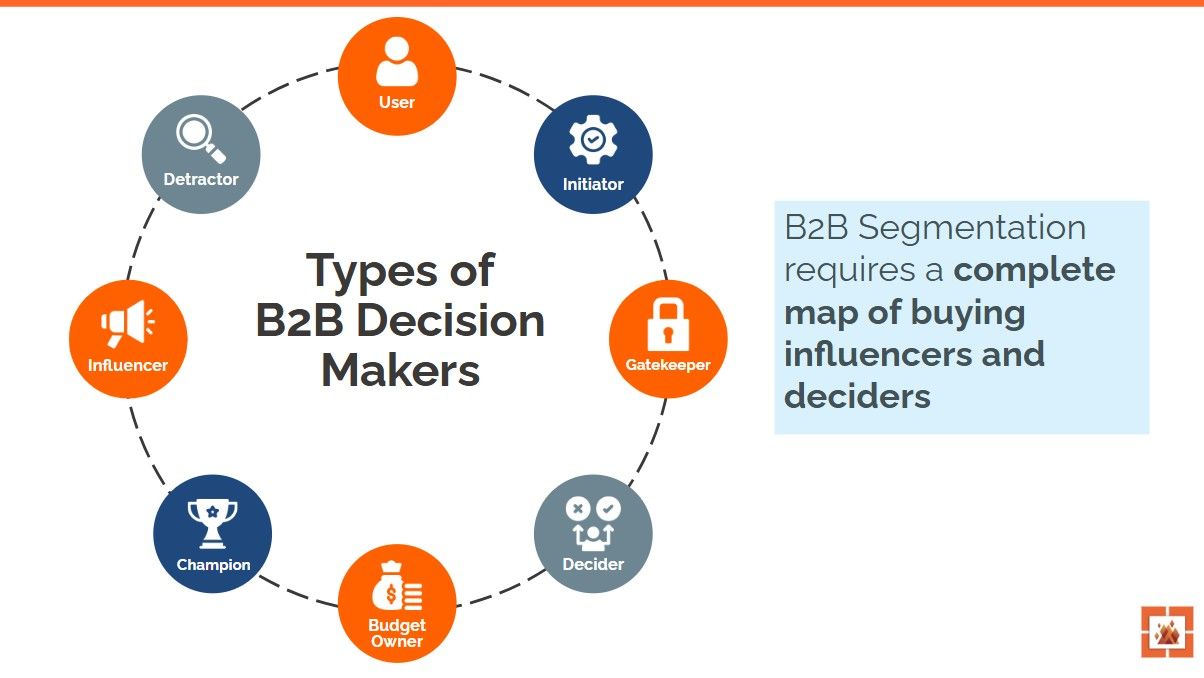

- Define the Ideal Customer Profile (ICP) Across Key Decision Makers: Narrow the target segment into a precise definition of your best-fit companies and map the key stakeholders within them, e.g. economic buyers, technical users, influencers, and champions, so targeting, messaging, and sales strategy align around the full buying committee.

You can download the slides that accompany this article here >.

B2B vs B2C Segmentation – Key Differences

Segmenting business markets (B2B) is more complex and nuanced than segmenting consumer markets (B2C). Harvard research observes that industrial (B2B) market segmentation is especially complicated because the same product can have multiple applications, different customers have widely varying needs, and it’s tricky to discern which differences truly matter for strategy. Unlike B2C companies that often segment by broad demographics or lifestyles, B2B firms focus on firmographics and add in role-based attributes. For example, B2B segmentation looks at factors like a target company’s industry, size, location, and technology, as well as the job title and function of key buyers.

In practice, this means a B2B marketer might tailor one approach for CFOs in large manufacturing firms and a different approach for engineers in mid-size tech companies – even if both are buying the same type of product. B2C segmentation, by contrast, might group individual consumers by age bracket, lifestyle, or behavior patterns.

Another key difference is the buying process: B2B purchases typically involve multiple decision-makers (buying committees), longer sales cycles, and informational buying criteria, whereas B2C decisions are often solo and can be driven by personal preference or emotion. Successful B2B segmentation must account for this complexity, ensuring that marketing and sales messages address the distinct priorities of, say, a technical user

and an economic buyer. As one industry source puts it, B2B audiences base decisions more on business need and impact (e.g. saving time, money, boosting ROI), whereas B

Expert Perspectives on B2B Segmentation

| Strong B2B Segmentation Strategy | Weak B2B Segmentation Strategy |

|---|---|

| Understand breadth and depth of market fundamentals | Focus on product features |

| Recognize and prioritize major market forces and change trajectories affecting their customers and business | Assumes the market is static |

| Drill down to need-based segments | Target product or service based categories |

| Understand offers and positioning that will MOVE potential clients to action | Have weak differentiation and me too positioning |

| Define segments you can win now and deliberately build toward over time | Chase attractive segments without a clear right-to-win or execution path |

Figure: Characteristics of excellent vs. weak market segmentation strategies (adapted from Malcolm McDonald, 2017). Effective strategies involve understanding markets in depth and targeting needs-based segments with specific offers and clear differentiation for each segment. Weaker approaches center on products rather than customer needs – for example, treating the whole market the same or focusing only on product categories – which leads to poor positioning and missed opportunities.

Seasoned marketing experts consistently stress that segmentation is fundamental to winning strategies, especially in B2B markets. Professor Malcolm McDonald calls market segmentation “one of the most fundamental concepts of marketing” and “the key to successful business performance.” He notes that it’s obvious there is no such thing as an average customer, so companies must identify distinct groups and tailor their offerings accordingly. In fact, an often-cited Harvard Business Review study by Christensen and colleagues found that around 90% of 30,000 new product launches failed due to poor market segmentation – underscoring how critical it is to get segmentation right.

McDonald argues that despite new marketing tech and data, needs-based segmentation remains the main route to commercial success. Rather than defaulting to simplistic splits (like demographics or product categories), the best practice is to segment by customer needs, behaviors, or benefits sought, especially in B2B where those needs can vary greatly even within the same industry.

Another marketing master, Philip Kotler, along with Benson Shapiro and Thomas Bonoma (early thought leaders on B2B segmentation), emphasize using multiple criteria in combination. They outline a “nested” approach: start by segmenting on broad factors like industry sector, company size, or geography (the macro-segmentation), then drill down further into each group by more specific factors – such as the customer’s operating characteristics or purchasing approach (the micro-segmentation stage).

This two-stage approach ensures B2B firms don’t stop at obvious groupings, but also consider deeper differences in needs or buying behavior. For instance, a company might first focus on the automotive industry vs. the aerospace industry (macro-level), and then within the automotive segment, distinguish between global OEM manufacturers and smaller parts suppliers, or segment by service-focused buyers vs. price-focused buyers (micro-level). The goal is to keep refining until each target segment is as clear-cut and internally consistent as possible. As Kotler’s work suggests, effective B2B segmentation yields a crystal-clear picture of the “typical” target customer in each segment . Only with this clarity can a firm craft tailored value propositions that resonate.

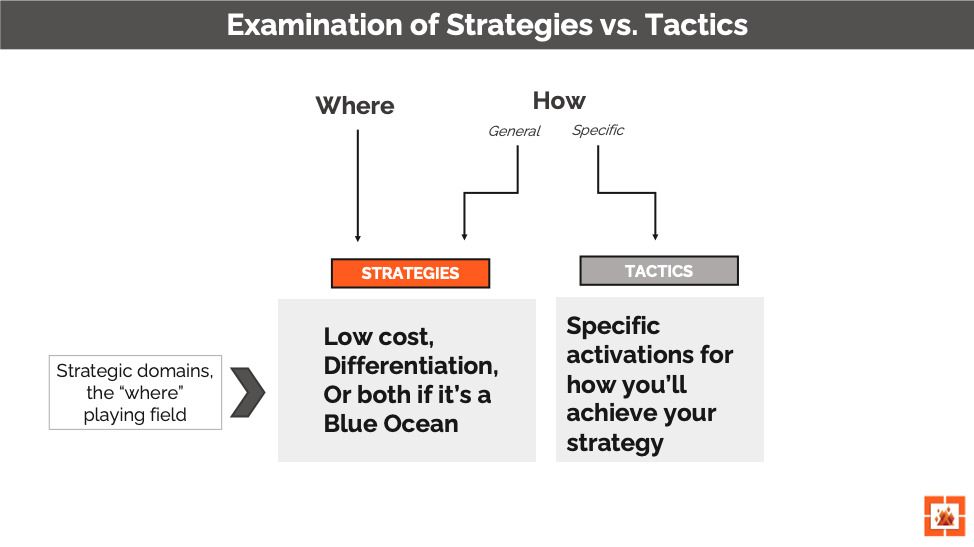

It’s also widely acknowledged that B2B segmentation must be actionable and tied to strategy. Renowned strategist David Aaker and others have written about focusing on segments where your brand can be relevant and differentiated. In their strategy book

Playing to Win, A.G. Lafley and Roger Martin (though drawing from B2C examples) echo a similar principle: companies need to choose “where to play” – i.e. which segments to compete in – and “how to win” in those segments by leveraging unique strengths. Legendary GE CEO Jack Welch famously put this into practice: he mandated that GE should only compete in markets where they could be the No. 1 or No. 2 player, and if not, they should exit or fix that business . This dictum essentially forced GE’s divisions to zero in on segments where GE had a true right to win (where its capabilities gave it a competitive advantage). The underlying message from these leaders: segmentation is strategic. It’s not just a marketing exercise but a company-wide choice about which customers you will serve – and serve well. Firms that segment thoughtfully (by customer needs, value, or other meaningful traits) and then align their products, services, and messages to those segments tend to outperform those that chase “average” customers with one-size-fits-all offerings.

How to Develop Criteria to Evaluate Your Market Segments

Once you move beyond surface-level groupings, a natural question emerges: how do you know if a segment is actually valid? In B2B markets, it’s easy to create segments that look elegant in a spreadsheet but collapse when you try to build strategy, allocate resources, or execute go-to-market plans. To avoid this, marketers and strategists commonly evaluate both market segments and customer segments against a consistent set of criteria. These criteria act as a quality bar, ensuring that segments are not only intellectually sound, but practically useful.

You can download all these B2B Segmentation slides, plus bonus material, here >.

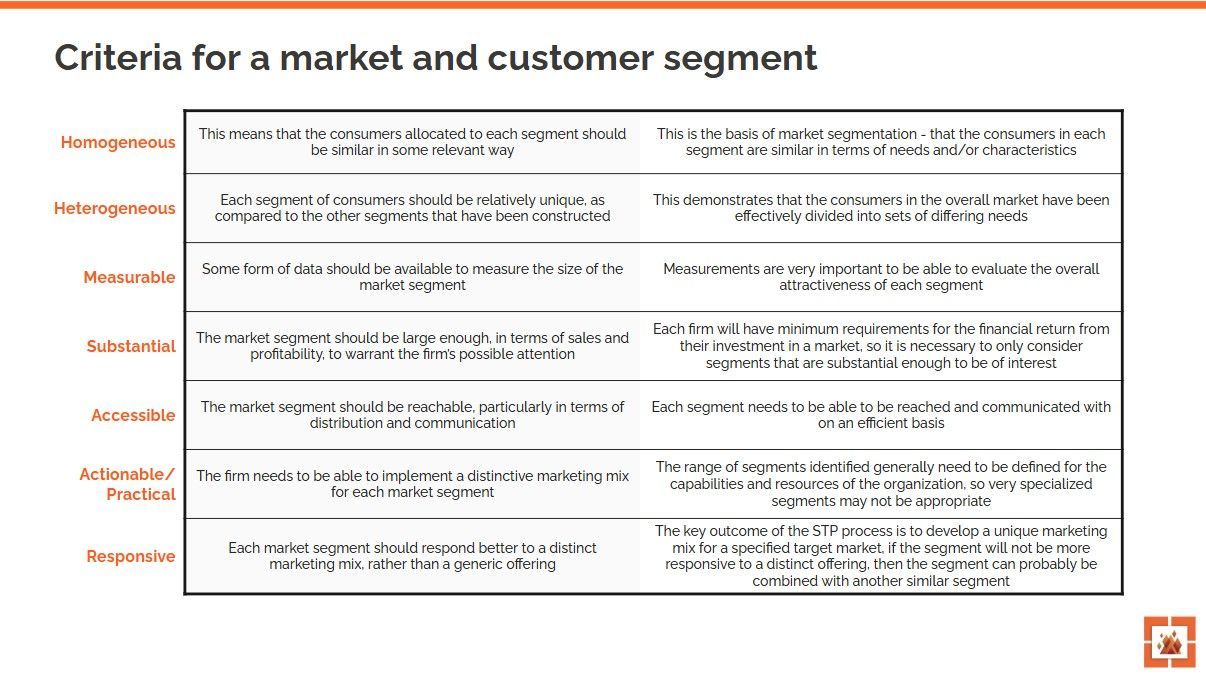

At the most basic level, a segment must be homogeneous internally. This means that the customers grouped together should be similar in ways that actually matter—such as their needs, buying criteria, operating constraints, or decision-making dynamics. If customers within a segment behave very differently or value different outcomes, the segment won’t support a coherent value proposition or marketing approach. At the same time, segments must be heterogeneous relative to one another. Each segment should be meaningfully distinct from the others; otherwise, the effort of segmentation adds complexity without improving clarity. Good segmentation increases contrast between segments while reducing variation within them.

Segments also need to be measurable. While not every dimension must be perfectly quantified, there should be enough data available to estimate the size, growth, and economic potential of a segment. Without some ability to measure a segment, it becomes difficult to prioritize investments or assess whether the opportunity is large enough to matter. Closely related is the requirement that segments be substantial. A segment may be analytically interesting, but if it cannot support meaningful revenue or profit over time, it is unlikely to warrant focused attention. Most firms have minimum thresholds for impact, and segmentation should reflect that economic reality.

Another critical criterion is accessibility. A segment must be reachable through viable channels—both in terms of marketing communication and distribution. If a firm cannot efficiently identify, target, and engage a segment, then even a well-defined group becomes impractical. Accessibility forces segmentation to stay grounded in how the business actually goes to market, not just how customers look on paper.

Beyond reach, segments must be actionable and practical. This means the organization has—or can reasonably build—the capabilities required to serve the segment with a distinct marketing mix. Over-segmentation can produce theoretically precise groups that exceed the firm’s operational or resource capacity. Strong segmentation strikes a balance between insight and execution, defining segments that the organization can realistically prioritize and support.

Finally, a strong segment must be responsive. The ultimate purpose of segmentation is to enable differentiation. If a segment does not respond more favorably to a tailored offering than to a generic one, then it is not truly a distinct segment. Responsiveness is often the clearest validation of segmentation quality: when a specific message, value proposition, or solution resonates disproportionately with one group, segmentation is doing its job.

Taken together, these criteria reinforce a simple but powerful idea: segmentation is only valuable if it leads to better strategic choices and better outcomes. Segments that are homogeneous, distinct, measurable, substantial, accessible, actionable, and responsive provide a foundation for clear positioning, focused investment, and sustained competitive advantage. Without meeting these criteria, segmentation risks becoming an academic exercise rather than a driver of real business performance.

The B2B Segmentation Process (“Laddering” from Macro to Micro)

Experts often describe B2B segmentation as a laddered or layered process. You begin at a high level and progressively drill down to finer segments, like narrowing down on a map. At the top level, a company might segment by “macro” criteria – broad categories such as industry vertical, use-case/application, or region. For example, imagine a software firm that serves both manufacturing and healthcare: it may decide to segment these as separate macro-markets because the industries are so different. Once a priority macro-segment is chosen, the next “rung” is identifying sub-segments within it. This could be by company size (e.g. large enterprises vs. mid-market firms) or by specific needs/use cases. A classic illustration is given in industrial marketing texts: a tire manufacturer could first target the automotive sector (vs. say, agricultural vehicles), then within automotive focus on large carmakers separately from small aftermarket parts dealers, and even tailor offerings by purchase criteria – some clients might seek the lowest price, while others require high reliability and service . By sequentially filtering the market – from broad to niche – the B2B marketer creates increasingly homogeneous groups. The final step is choosing target segments among these that align best with the firm’s strengths and objectives. It’s at this stage that the firm decides, “Which of these segments are the most attractive and feasible for us to win?”

This laddering approach is important because B2B markets often segment along multiple dimensions simultaneously. A simple one-factor segmentation (e.g. just by industry) may be too coarse to be useful. Instead, combining dimensions yields segments that are more actionable. A well-segmented B2B market might be defined as, for instance, “Mid-sized financial services companies in North America that need cloud-based data analytics and prioritize vendors who offer strong customer support.” That description incorporates firmographic info (industry, size, geography) and behavioral needs (analytics + support) – a far more precise target than “financial services sector” in general. Such precise segmentation helps in tailoring marketing messages, sales pitches, and even product development to match the segment’s unique profile. Research by Shapiro and Bonoma on industrial markets introduced five broad categories of variables to consider: Demographics (industry, size, location), Operating Variables (technology, usage rate, etc.), Purchasing approaches (procurement process, criteria), Situational factors (urgency of order, application use), and Personal characteristics of buyers (e.g. risk attitude, loyalty) . Great B2B segmentation often uses a mix of these – starting from the top (demographic macro segments) and then nesting the more specific criteria inside. The result is a segmentation that reflects the real-world complexities of the market, rather than an oversimplified view.

Common Challenges in B2B Segmentation (and How Firms Overcome Them)

Even with a sound process, B2B segmentation comes with unique challenges. Below are some of the biggest challenges that arise repeatedly – and examples of how companies have tackled them to win in their markets:

- Multiple Decision-Makers and Personas: In B2B sales, you’re rarely targeting just one person – there’s often a buying committee or multiple influencers (e.g. a technical evaluator, a financial approver, end-users, etc.). Each has different priorities, which can muddle segmentation if you only define the segment at a company level. Leading firms solve this by incorporating persona segmentation and personalized marketing. For example, GE Healthcare realized that even within a single hospital, a radiologist, a CFO, and a technician each care about different things – and a doctor in the UK vs. one in India face different contexts. Historically, GE Healthcare’s marketing gave “the same message to all of those people,” but they restructured to tailor content to each role and region. By segmenting their audience not just by account, but by role (job function) and needs, they humanized their B2B marketing and saw a surge in engagement. The lesson: Don’t treat a client organization as one monolithic audience – segment by key personas within it. This often means developing targeted messaging for, say, engineers vs. executives, or procurement managers vs. end-users, ensuring each segment hears what matters most to them.

- Shifting Customer Needs & Commoditization: B2B markets can evolve – sometimes customers’ priorities change (e.g. a greater focus on cost savings) or a product that used to be a specialty becomes a commodity. If a company doesn’t adjust its segmentation, it can lose out. A classic example is Dow Corning in the early 2000s. They faced stagnation as their core product (silicone materials) was commoditizing and competitors undercut prices. A strategic review led to a fresh needs-based segmentation of their customer base . They discovered that across industries, customers fell into four distinct segments ranging from “pure innovation seekers” (who valued technical support and R&D from Dow) to “price seekers” (who just wanted basic silicone at the lowest price) . Dow Corning realized it was over-serving the price seekers with an expensive, high-touch model those customers didn’t need. The company’s bold response was to create a whole new business unit and brand (Xiameter) to serve the price-driven segment. Xiameter sold standard silicone in bulk via a no-frills online platform – stripping out custom services and salesperson visits in exchange for prices about 15% lower. Importantly, this wasn’t just a blanket discount; it was a different business model tailored to that segment’s needs (e.g. enforcing minimum order sizes and only online ordering to keep costs down) . This move let Dow Corning “embrace” commoditization on its own terms – they retained price-sensitive customers by giving them a channel optimized for price, while the main Dow Corning business continued to focus on innovation-seeking customers who valued full service. The result was a huge success and became a textbook case of B2B segmentation: by splitting the market and offering a targeted value proposition to a neglected segment, Dow Corning captured new growth and defended its turf . The key takeaway is that when customer needs shift (e.g. toward price, or any other dimension), re-segment your market and consider new approaches rather than trying to force all customers into one model.

- Technological and Channel Changes: Changes in how customers research and buy can also necessitate new segmentation. With the rise of digital channels, many B2B buyers now educate themselves long before engaging a sales rep. This has pushed companies to segment by customer journey stage or behavior. GE Healthcare’s marketing transformation is again instructive: they “woke up to the fact” that customers were 70% of the way through their decision before talking to sales . To adapt, GE Healthcare segmented content by where the customer is in the journey (e.g. providing early-stage educational content targeted to potential customers before they even enter a sales funnel). They invested in marketing automation and tracking so they could nurture leads over a long cycle and deliver the right information at the right time . This approach is akin to B2C-style segmentation by behavior (something historically less common in B2B) – tracking interactions and segmenting by interest level or engagement, not just firmographics. Another angle is the shift to e-commerce in B2B: companies now segment by preferred buying channel, offering different paths for those who want self-serve online purchasing vs. those who prefer traditional account managers. Adapting to technology shifts often means creating new segments (like “digital-first customers”) and ensuring your strategy addresses them (for example, by building an e-commerce platform for a segment that values convenience). Fast-follower vs. innovator dynamics also come into play here. Companies that foresee a new segment emerging (due to technology) can get ahead – for instance, IBM saw an opportunity in the 1990s to provide integrated solutions as businesses started networking their IT systems. They reorganized around customer-centric segments (instead of product silos) to become a one-stop solution provider . Others, who are late, must segment and target defensively after a competitor has proven the segment. In either case, being attuned to how technology is changing customer behavior is vital to updating your segmentation strategy in time.

- Choosing Target Segments and “Where to Play”: Another major challenge is deciding which segments to focus on – especially for large or diversified B2B companies that

could chase many opportunities. Spreading too thin undermines success, but focusing on the wrong segment can be just as fatal. The solution top strategists recommend is to evaluate segments based on both attractiveness (size, growth, profit potential) and fit with your capabilities. This echoes the “right to win” concept: choose segments where your firm has unique strengths or can build a sustainable advantage. We saw this with Jack Welch’s mandate for GE to be #1 or #2. That rule effectively forced GE to exit segments where it couldn’t lead, and double down on those where it could – a brutal but effective form of segmentation at the business portfolio level . Another example is how many SaaS companies start in a niche segment they know they can dominate (often a specific industry or use-case) before expanding. They identify a beachhead segment where their product perfectly fits an urgent need – winning there gives them a foothold and credibility to later tackle adjacent segments. The general principle is prioritization: great segmentation isn’t just dividing the market, it’s also picking the best target segments and then aligning your resources to serve them better than anyone else. As Lafley and Martin put it, strategy is fundamentally about making choices – you “win” by choosing the right place to play and then executing a tailored strategy for that chosen segment. Companies that rigorously evaluate where they can be distinctive (through their technology, relationships, cost structure, etc.) and concentrate on those segments tend to outperform those who chase every possible customer. In practice, this might mean, for example, a manufacturing supplier decides to focus only on the aerospace segment (because of a technical advantage there) and not pursue the automotive segment as aggressively – even if automotive is larger – because they know aerospace customers value their unique materials expertise more. Such discipline in segmentation can be tough (it requires saying no to some sales), but it leads to far stronger positioning in the segments you do serve.

B2B Segmentation in Action: Notable Examples

Let’s look at a few illustrative examples (past and present) of B2B segmentation driving strategy shifts, to see how theory translates to real outcomes:

- General Electric’s Portfolio Segmentation – Balancing Old and New Segments: As a conglomerate, GE has always had to think in terms of segmenting which industries and markets to participate in. Under Jack Welch in the 1980s and ’90s, GE applied a Darwinian segmentation rule: if a business unit couldn’t be one of the top two in its market segment, GE would consider exiting that segment . This led GE to divest or fix underperforming units and aggressively build strength in segments where it saw leadership potential. For instance, GE exited the small consumer electronics segment (where it lacked an edge) and doubled down on segments like medical imaging and jet engines, where it had technology leadership. In the 2000s and beyond, GE also segmented markets by innovation level – launching Ecomagination (focusing on eco-friendly products) and edge initiatives for emerging market segments (like developing low-cost equipment for India and China separately from high-end segments in developed markets). Although GE’s fortunes have varied, the lesson is their willingness to segment and re-segment their portfolio of businesses in response to global changes. They treated entering new industry segments (like renewable energy) or spinning off segments (like the recent separation of GE’s healthcare, energy, and aviation arms) as strategic segmentation decisions to unlock value.

- IBM in the 1990s – From Product-Centric to Customer-Centric Segmentation: In the early ’90s, IBM was struggling. The company was organized around product divisions (mainframes, PCs, software, etc.), but customers were increasingly wanting integrated solutions that solved business problems, not a pile of separate hardware and software. When Lou Gerstner took over as CEO, he famously halted a plan to break IBM into smaller product-based companies. Instead, IBM embarked on a major re-segmentation and reorganization around customer types and needs. Gerstner observed that clients “wanted help putting everything together,” not dealing with a different IBM unit for each piece . So IBM shifted to market-based segments – for example, creating teams focused on the banking industry, or on small-to-medium businesses – cutting across product lines. They also introduced the concept of IBM as a service provider (the birth of IBM Global Services) to offer one-stop solutions. This was essentially IBM choosing new segmentation dimensions: by industry vertical and by customer size, and focusing on selling solutions rather than just products. The payoff was significant: IBM’s alignment with the market made it much more “easy for customers to do business with” them and helped restore growth . This example highlights how changing your segmentation approach can be transformational. IBM moved from “What can we sell?” (product segments) to “What does the customer need?” (customer segments), a hallmark of successful B2B strategy.

- Honeywell – Segmentation by Industry and Needs: Honeywell, another diversified B2B giant (spanning aerospace, automation, building technologies, materials, etc.), provides an example of multi-layered segmentation in practice. At the highest level, Honeywell is segmented into strategic business groups aligned by industry (Aerospace, Building Technologies, Performance Materials, Safety & Productivity Solutions, etc.). This is a form of macro-segmentation ensuring each unit focuses on its specific market domain. Within those groups, Honeywell further segments by customer application and needs. For instance, in aerospace they segment OEM aircraft manufacturers vs. aftermarket service customers; in building technologies, they segment commercial buildings vs. residential, and even by verticals like healthcare facilities vs. data centers (since each has distinct needs for environmental controls). Honeywell’s go-to-market teams develop segment-specific value propositions – a hospital might get an integrated “smart hospital” solution pitch, while an airport gets a different bundle – even though both use “building technologies” from Honeywell. Moreover, Honeywell adapts to new segments emerging from technology shifts, such as the segment of customers interested in IoT-enabled solutions (the “connected” segment). By segmenting and offering IoT-based services (like predictive maintenance) separately from traditional product sales, Honeywell targets forward-looking customers with a tailored approach. This ability to ladder from broad industry segments down to very specific use-case segments (and create new segments when technology enables new offerings) has helped Honeywell remain competitive across very different markets. It shows that even in very old-line industries, thoughtful segmentation (paired with targeted product strategy for each segment) is key to sustaining growth.

- Dow Corning’s Xiameter (2002) – A Bold Segmentation Play: We discussed this above in the challenges, but it merits emphasis as a stand-alone example. Dow Corning essentially split its market in two when it launched the Xiameter platform. This was unusual at the time – treating a set of customers as so different that they get a wholly separate channel and brand. By doing so, Dow Corning acknowledged that the “price seeker” segment was incompatible with the high-service model needed by the “innovation seeker” segment . Rather than force one approach on all, they targeted each segment on its own terms. Xiameter’s success (it captured significant volume and operated profitably at lower margins) validated the idea that one company can use multiple segmentation strategies in parallel – essentially running a multi-segment strategy with tailored offerings for each. This is a form of tiered segmentation that other B2B firms have since emulated (for example, software companies offering both a self-serve low-price product for small businesses and an enterprise version with full support). The Xiameter case also highlights an important point: effective segmentation sometimes means you have to accept trade-offs (e.g. a simpler product, fewer services for the low-cost segment) and not try to be all things to all customers. By differentiating the value propositions, Dow Corning protected its premium segment’s value while still competing hard in the commodity segment – turning what could have been a lose-lose situation into a win-win.

- Modern SaaS Companies – Segmentation by Size and Behavior: In the software-as-a-service world, segmentation is often very visible through product tiers and specialized sales teams. Take CRM software leader Salesforce as an example. Salesforce segments its market by business size and complexity: it has an entire “Small Business” edition and sales unit geared toward small and mid-sized clients (with simpler, lower-cost offerings), and a separate “Enterprise” segment with a high-touch salesforce targeting Fortune 500 firms and offering advanced, customizable solutions. The needs of a 10-person company vs. a 10,000-person company differ drastically, so Salesforce’s segmentation ensures each gets the appropriate level of service and product complexity. Another SaaS example is HubSpot, which started off focusing on small businesses with inbound marketing needs. By initially segmenting out large enterprises (which were served by other software), HubSpot built a product ideally suited to the small business segment and became a leader there. Only later did they introduce an enterprise tier to move upmarket, essentially adding a new segment once they had the capacity to serve it. Stripe, the online payments company, similarly segmented early on by targeting startups and developers (neglected by big banks). That focus allowed it to win that segment, then expand to larger online retailers and even offline businesses with tailored solutions. The common thread is that successful B2B startups often begin with a very specific target segment (sometimes defined by a combination of industry, size, and a particular “job to be done”), dominate it, and then broaden to adjacent segments. This phased segmentation strategy is a way to manage risk and gain credibility step by step. It also shows how segmentation is an ongoing, dynamic exercise – as a company grows, it may re-segment its market or add new segments to continue expanding, all while maintaining distinct strategies for each.

- Tesco’s Clubcard (A B2C Segmentation Example):

While our focus is B2B, it’s worth noting a famous B2C example to illustrate segmentation principles. UK retailer Tesco in the 1990s launched the Clubcard loyalty program, which collected detailed data on customer purchases. Tesco used this data to perform granular segmentation of its customer base and then tailored promotions and product offerings to different segments (e.g. targeting a “young family” segment with coupons for diapers and kids’ foods, or a “upmarket foodie” segment with premium organic product offers). This data-driven segmentation is credited with helping Tesco leapfrog competitors in the UK. Tesco also segmented its store formats to serve different needs: Tesco Express convenience stores for urban, small-basket shoppers, vs. large Tesco Extra hypermarkets for one-stop family shopping, and even Tesco Homeplus for furniture/home goods in suburban markets . By aligning store formats and product mix to distinct segments and shopping occasions, Tesco maximized its reach. The Clubcard example shows how understanding sub-groups of customers (through data) can inform everything from marketing to operations. In a B2B sense, the parallel would be using detailed customer research to identify segments by behavior or value, and then adapting your service model for each (much like how GE Healthcare used marketing automation data to segment and personalize outreach, or how Dow Corning used purchasing behavior to segment price-sensitive vs. service-sensitive clients). The core idea is the same: know your segments deeply, then act on that knowledge to tailor the experience.

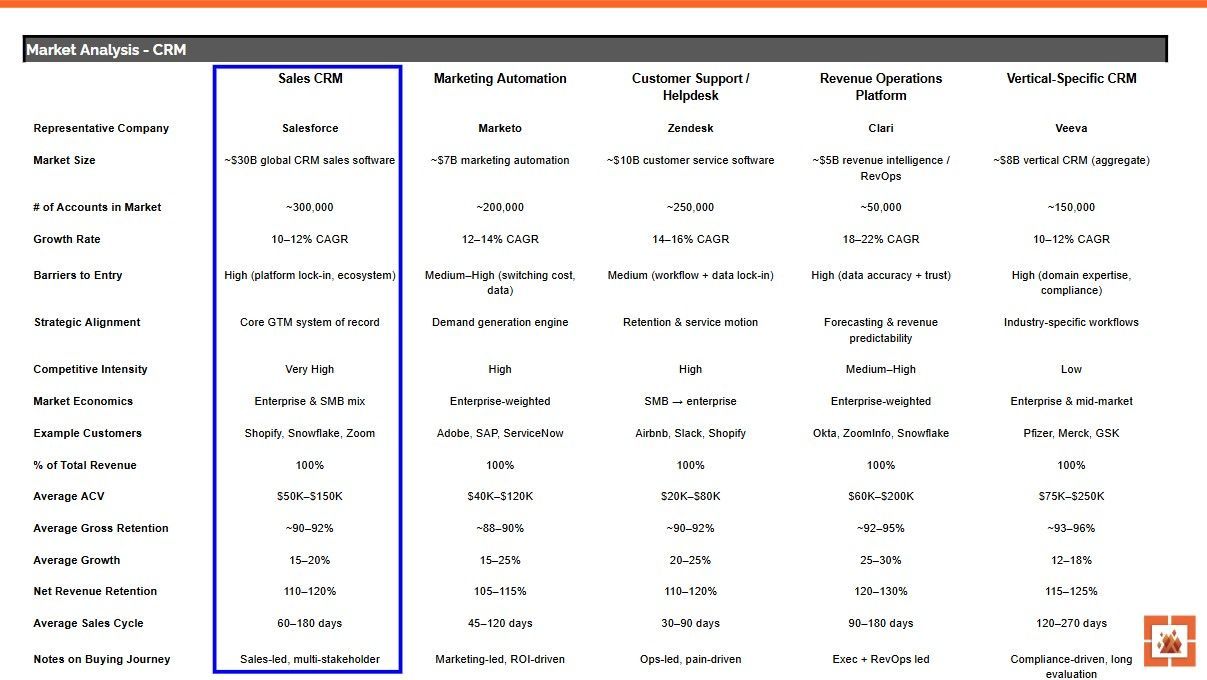

An in Depth Look: The B2B CRM Market and Customer Segmentation

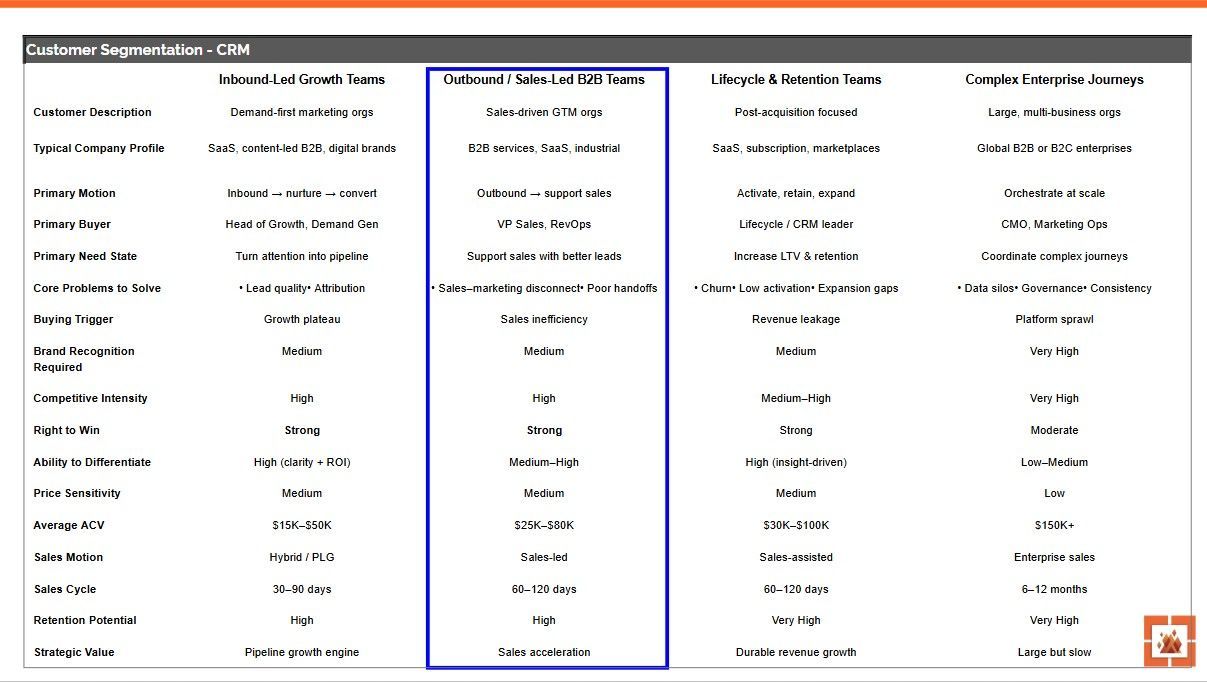

To make these concepts concrete, the examples below walk through segmentation in two steps using the CRM category. First, we look at the CRM market itself, breaking it into distinct market segments (such as Sales CRM, Marketing Automation, and Revenue Operations) and evaluating each based on size, growth, competitive intensity, and strategic fit. This helps answer the question, “Where should we play?”

Next, we zoom in on one of those market segments (Sales Team Focused CRMs) and apply a second table to evaluate customer segments within that market, comparing different need states, buying dynamics, right-to-win, and competitive pressure. Together, these tables illustrate how strong B2B segmentation moves from market-level structure to customer-level focus, and how each layer informs smarter prioritization, positioning, and go-to-market decisions.

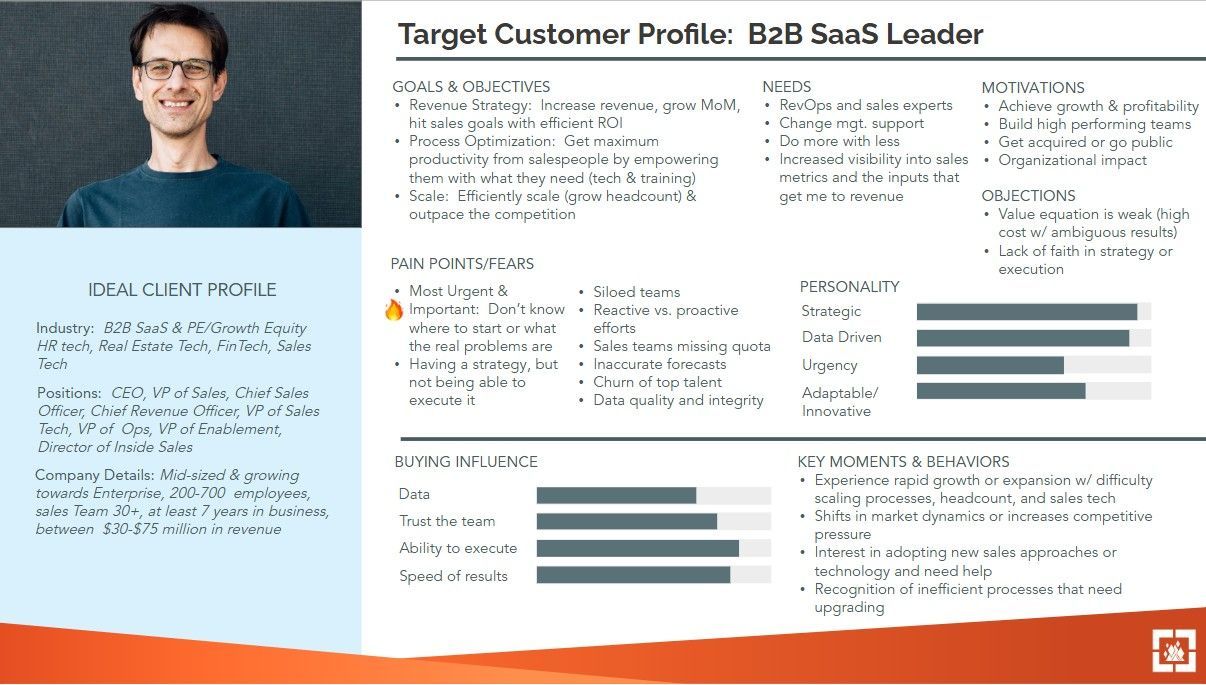

Choosing a Customer Target & Creating a Profile

Once a CRM customer segment is selected as the main target, the work doesn’t stop at naming the segment—it deepens into understanding the people inside it. This target customer profile is an example of what that looks like in practice for a B2B SaaS leader evaluating a CRM. After identifying the segment (for example, mid-sized B2B SaaS companies with complex revenue motions), the profile translates that abstract segment into a real decision-maker with concrete goals, pressures, motivations, and constraints. By fleshing out objectives, pain points, buying influences, and behavioral triggers, teams can move from “who we’re targeting” to “how this customer actually thinks and buys.” Profiles like this are how segmentation becomes actionable: they inform positioning, clarify value propositions, guide CRM feature prioritization, shape sales conversations, and align marketing, sales, and product teams around a shared understanding of the customer. In short, once a target segment is chosen, profiles like this turn strategy into execution.

Why B2B Segmentation Matters More Than Ever

B2B segmentation is not a one-time task but a continuous strategic discipline. Customer needs evolve, new segments emerge (for example, the rise of the “as-a-service” segment in industries like manufacturing, where customers prefer outcomes or subscriptions over buying equipment outright), and competitive dynamics shift. Companies that have a solid segmentation framework and thinking approach can sense these changes earlier by keeping a close eye on each segment’s trends.

Moreover, with the proliferation of data and analytics, B2B firms have more tools to conduct fine-grained segmentation – from predictive lead scoring (segmenting by likelihood to buy) to customer success analytics (segmenting by product usage patterns to drive upsell and retention). The experts universally agree that focusing on the right segments is a force-multiplier for business performance. It allows for more efficient marketing (you’re not casting a wide net and hoping), more effective sales (sales teams can specialize by segment and really become experts in their customers’ context), and even guides innovation (knowing unmet needs in a segment can spark new product ideas). As one Nielsen study noted, companies that outgrow their competitors tend to derive a higher portion of revenue from carefully personalized offerings – essentially, from segmented strategies – than slower growers.

In summary, B2B segmentation is different from B2C in its complexity, but the core goal is the same: to identify groups of customers who have meaningful common needs or traits, so that you can serve them better than a more generalized approach ever could. The best B2B practitioners treat segmentation as the cornerstone of their strategy – informing everything from product development to channel strategy. Thought leaders from Kotler to McDonald to Lafley have all, in their own way, preached the mantra of “divide and conquer” in markets. When done well, segmentation clarifies where to focus and how to win, which is incredibly liberating for a business. Instead of trying to be “everything to everyone,” the company can double down on being the best for someone – namely, the customers in its chosen segments. And as the examples of IBM, GE, Dow Corning, and others illustrate, that focus can lead to remarkable shifts in fortune, turning struggling businesses into market leaders. Whether it’s an established industrial giant reorganizing around customer segments, or a startup carving out a niche, segmentation is often the decisive factor between companies that merely survive and those that thrive.

You can download all the B2B Segmentation slides from this article, plus bonus material, here >.

Adam Fischer is a marketer with 10+ years of experience in brand management and digital marketing. He’s challenged conventional assumptions and taken bold moves to drive growth for small businesses like Dogeared Jewelry to multi-billion-dollar companies like CVS Health and Nature Made Vitamins. He leverages his B.S. in Philosophy from Northeastern University to ask questions that get to the heart of business issues, while his MBA in Marketing from the Thunderbird School of Global Management at ASU translates management philosophy into real strategic growth.

Insights to fuel your marketing business

Sign up to get industry insights, trends, and more in your inbox.

Contact Us

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.

Latest Posts