Bad Strategy & Good Strategy: How to Tell the Difference

By Adam Fischer • June 30, 2023

Good strategy and bad strategy are always fighting each other. Sadly, it looks like good strategy loses the battle; Forbes cites less than 10% of leaders exhibit adequate strategic skills.

Richard Rumelt’s classic book, Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why it Matters, acts as an antidote to books with highbrow strategic fluff. This article summarizes key points form the book with frameworks and slides to help you execute the ideas. The focus is a bit more on the signs of bad strategy in an effort to help you avoid the pitfalls.

What Does a Good Business Strategy Look Like?

Good strategy is coherent action backed up by an argument, an effective mixture of thought and action with a basic underlying structure I call the kernel. A good strategy may consist of more than the kernel, but if the kernel is absent or misshapen, then there is a serious problem.

- Richard Rumelt, Good Strategy/Bad Strategy

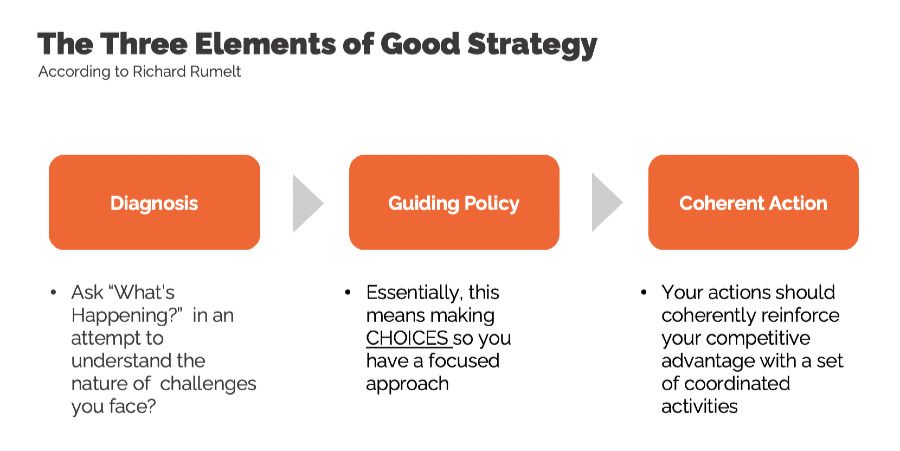

Similar to how Plato grappled with defining the “good,” defining what “good strategy" looks like can be problematic. Rumelt’s book offers three essential guideposts for good business strategy:

A Diagnosis

This is where you ask (similar to our OCCAM’s Razor for Strategic Thinking) the question “What’s Happening?” and break down noise and complexity by offering the critical factors of the situations.

A Guiding Policy

Essentially, this means making choices so you have a focused approach

Coherent Action

The word coherent is carefully chosen here; your actions should coherently reinforce your competitive advantage with a set of coordinated activities.

What are the Sources of Power in Good Strategy?

Good strategy is born out of reinforcing actions that harness collective power to the point of greatest impact, like a perfect baseball swing where the bat smacks the ball right on it's sweet spot to generate the greatest kinetic energy. These sources of power provide the necessary resources, leverage, and decision-making capabilities to drive the strategy forward.

According to Rumelt, the sources of power include:

- Leverage: This involves analyzing the competitive landscape and identifying areas where the organization has an advantage or where competitors are struggling. By strategically exploiting these imbalances, organizations can gain a competitive edge and make resourceful decisions that maximize their chances of success.

- Constraints: Rather than seeing constraints as limitations, organizations can view them as opportunities for innovation and creativity. By understanding and embracing constraints, organizations can find unique ways to leverage their resources and make strategic decisions that effectively address their limitations.

- Proximate objectives: Proximate objectives are specific goals that are essential steps towards achieving the overall strategic goal. By setting objectives that are achievable and realistic, organizations can maintain a sense of momentum and progress, leading to increased motivation and morale among employees.

- Chain-link systems: A chain-link system involves the coordination and alignment of various activities and objectives within an organization. Each action in the chain is carefully designed to contribute to the overall strategic objective, creating a cohesive and well-coordinated strategy.

- Design: Effective strategies often resemble designs more than decisions. They are meticulously constructed, not merely chosen. Strategies are designed to align various elements, policies, and activities to focus on competitive advantage. Striking the right combinations can yield substantial gains, while misalignment can be costly.

- Focus: Concentrating efforts on fewer, yet more significant, objectives often yields greater rewards. Business strategists may choose to dominate a smaller market segment over a larger one, focusing on targets that capture attention and influence opinion. Perceived effectiveness influences support and participation.

- For example: Completely transforming 2 schools can have a more profound impact on public opinion than making a 2% improvement in 200 schools.

- Competitive advantage: Businesses must leverage their unique capabilities to deliver lower costs or greater perceived value. Competitive advantage hinges on the ability to sustain it, often through isolating mechanisms like patents, reputation, relationships, or economies of scale. The true art of competitive advantage lies in enhancing its value through strategic insights.

- Growth through acquisitions – Dynamics – Inertia – Entropy

How Does Complexity Affect Strategic Concepts?

Complexity plays a huge role in shaping strategic concepts. Strategic concepts should be developed taking into account the need to navigate the overwhelming complexity of the business landscape.

Complexity stems from numerous interconnected factors, such as technological advancements, market dynamics, and socio-political influences. These factors form a web of relationships that often defy easy categorization or prediction. Rumelt emphasized the importance of understanding complexity in his work, arguing that the failure to comprehend complexity often leads to template-style strategies that lack coherence and fail to address the underlying problems.

Developing a coherent strategy requires deep understanding of the environment, the competition, and the organization's own capabilities. It involves identifying sources of advantage and patterns of advantage that can be leveraged for success. This understanding allows strategists to navigate complexity, identifying proximate objectives that contribute to achieving larger strategic goals.

Let's consider a case with Wal-Mart. Their strategy of offering low prices and providing a one-stop shopping experience for customers was a well-managed chain-link system that tackled the complex challenge of reducing storage costs and improving logistics. It involved innovations in supply chain management, leveraging economies of scale, and streamlining operations to offer lower prices to consumers.

Complexity significantly influences strategic concepts. Understanding and navigating overwhelming complexity is essential for effective strategic decision-making.

Developing a Coherent, True Strategy

Developing a coherent, true strategy is crucial for any organization to achieve its goals and objectives effectively. A true strategy goes beyond generic template-style strategy and takes into account just how complex our world and business landscape is. It involves identifying the key challenges and patterns of advantage in the competitive situation and leveraging them to create a competitive advantage. It requires a deep understanding of the sources of power and the ability to translate them into pragmatic ideas and coherent action. Developing a coherent, true strategy involves setting clear financial goals and proximate goals, which serve as milestones towards achieving the overarching strategic objectives. Aligning the organization's actions and resources towards a pivotal objective while also keeping an eye on blue-sky objectives for future growth and innovation are key.

For a deeper look at what strategy is, see our article on:

Good Strategy Is Simple, But Not Simplistic.

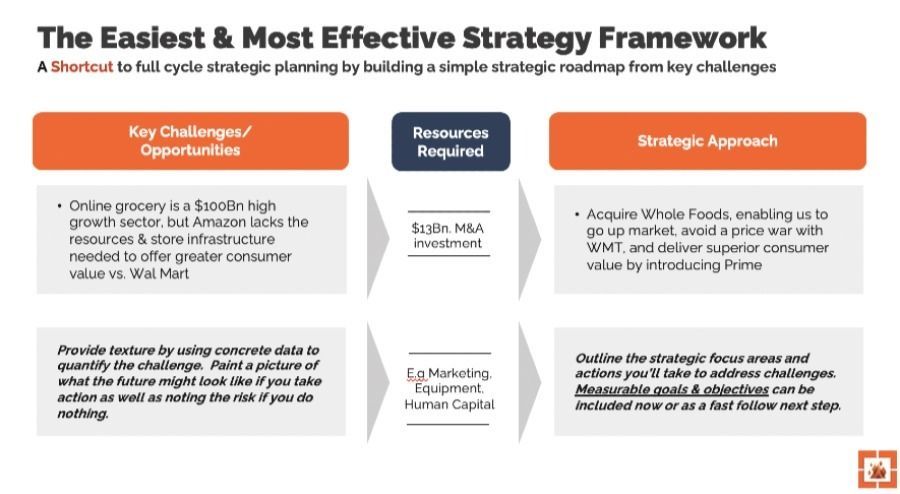

With that in mind, here's the fastest way to side-step a convoluted strategic planning process.

We can admit there's no perfect shortcut to good strategy, BUT this is the best framework I've found that can be employed to layout strategies in a pinch. Does this slide example with Amazon meet the criteria laid out by Rumelt? Is the diagnosis, guiding policy, and coherent action evident? I believe so; that's why I think this "shortcut" can get the job done.

If you want a framework with all the strategic bells and whistles, our GOST framework is comprehensive and what you're looking for. Check out our:

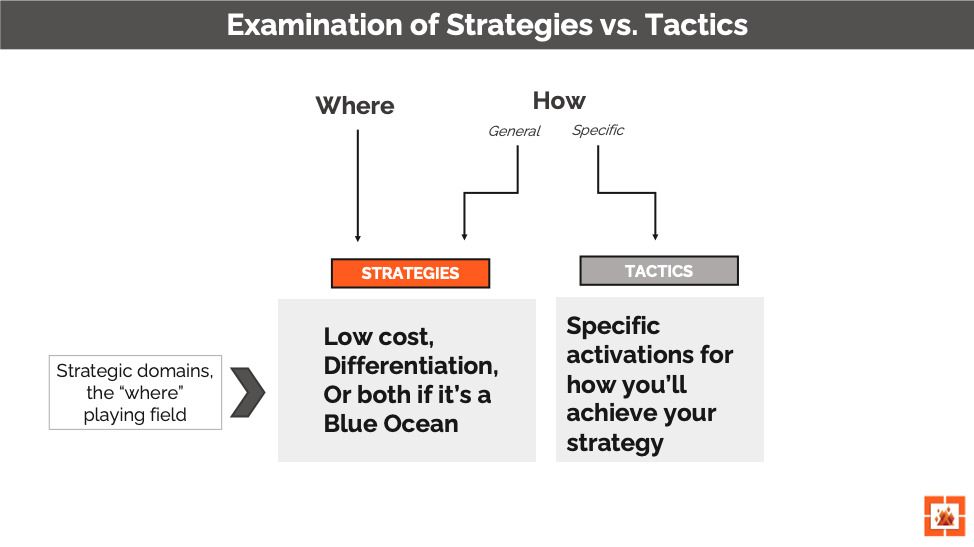

The Easiest Way To Know If You Have A Real Business Strategy

We’ve all heard that “the essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.” I have a simple and easy way to apply this idea, making it a pressure test to help you spot a true strategy from a false one. You must be able to say “NO, I won’t do this” in order to have a bona fide strategy. Let me explain. If you were a hospital, you wouldn’t be able to say “No, patient safety is NOT a priority.” Every hospital has patient safety as a critical, table stakes priority. Therefore, it’s not a strategy, because it’s not differentiated from any others hospitals. ALL hospitals should have patient safety as a focus, so it doesn’t pass muster as a true strategy. This hospital example illustrates one of the most widespread bad strategies out there; labeling what everyone already does in your industry, and perhaps must do as, as part of your strategy.

Sometimes a look at what to avoid helps strengthen your vision for what you need to do.

Examination Of What Makes Good Strategy Become Bad Strategy

Bad strategy is not simply the absence of good strategy. It grows out of specific misconceptions and leadership dysfunctions. Once you develop the ability to detect bad strategy, you will dramatically improve your effectiveness at judging, influencing, and creating strategy.

- Richard Rumelt, Good Strategy / Bad Strategy

To detect a bad strategy, look for one or more of its four major hallmarks:

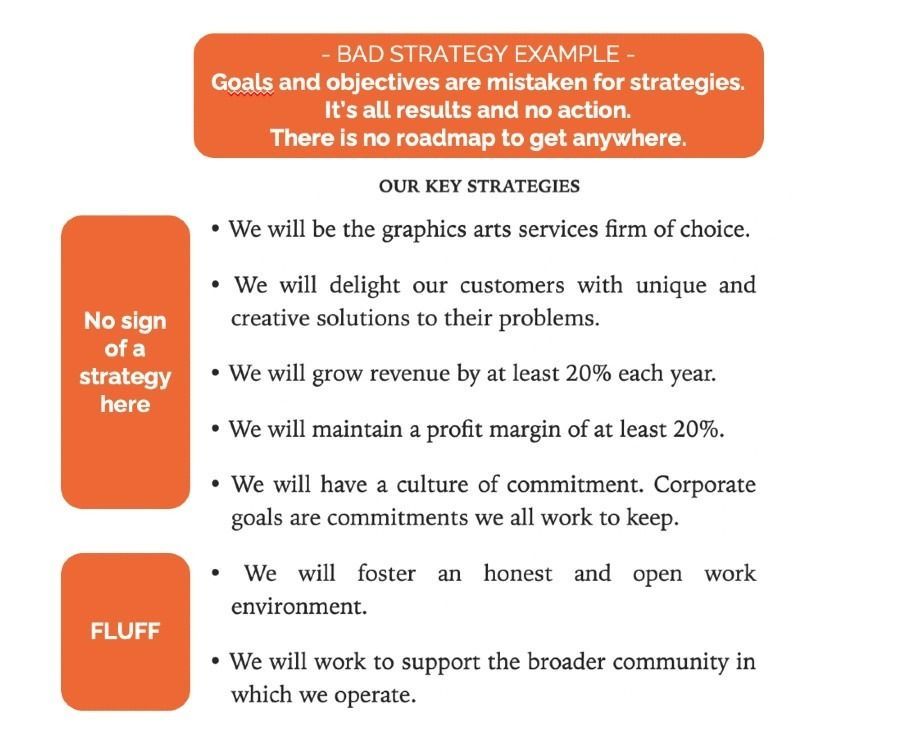

Fluff

Fluff is a form of gibberish masquerading as strategic concepts or arguments. It uses “Sunday” words (words that are inflated and unnecessarily abstruse) and apparently esoteric concepts to create the illusion of high-level thinking.

Failure to Face the Challenge

Bad strategy fails to recognize or define the challenge. When you cannot define the challenge, you cannot evaluate a strategy or improve it.

Mistaking Goals for Strategy

Many bad strategies are just statements of desire rather than plans for action.

Bad Strategic Objectives

A strategic objective is set by a leader as a means to an end. Strategic objectives are “bad” when they fail to address critical issues or when they are impracticable.” “The business was organized into a large design group and three sales departments: Media sold to magazines and newspapers, Corporate sold to corporations for catalogs and brochures, and Digital sold mainly to Web-based customers.

Here's a simple list of some signs of bad strategy:

- No focus, full of fluff

- Avoid facing brutal truths

- Does not start with question

- Is too ambitious and not executable

- Does not link to core capabilities and is not reinforced

- You can’t say NO to it

- Often focused on goals

Rumelt calls out an especially bad example of a strategy one of his clients shared: "Our strategy is customer-focused disintermediation." Does it get any fluffier than that?! A strategy is not abstract orders and jargon. It's not even all about the future or where you hope to be.

Strategies can – and often should be – proximate.

What problems are you facing today? Have you examined and analyzed anything so you can find your strategy?

Good and bad strategies can become difficult to identify during business planning. Once planning season is underway, you may find yourself presenting strategies to senior management, getting feedback, and simply executing a "Frankensteined" version of what you strategically want to do, plus what senior management gave as feedback during the planning process. Business planning is rarely a creative, swing for the fences affair. Senior leaders, especially in large corporate environments, know how difficult it is to execute. This inclines them to water down strategy into something much easier to execute operationally. Take a look at your strategies and intentions before and after business planning feedback happens. Do your strategies get stronger and clearer, or weaker but perhaps tactically easier to execute?

If there's no problem, there's no strategy.

- Strategy Kiln

Conclusion

Don't turn to the dark side of bad strategy. Confront brutal truths with courage, but don't be the marvel super hero who thinks it's all about bold entrances and over the top action scenes.

Employ patience and deep thinking to find simple solutions to the problems you face. Everyone's surprised when they see a real strategy, because they're scarce.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple two months before bankruptcy, his simple strategy was to cut the Apple computer line down from 15 to just 1. Wall Street thought it spelled certain doom, but his proximate strategy was to survive. Would you have been able to make that call?

Adam Fischer is a marketer with 10+ years of experience in brand management and digital marketing. He’s challenged conventional assumptions and taken bold moves to drive growth for small businesses like Dogeared Jewelry to multi-billion-dollar companies like CVS Health and Nature Made Vitamins. He leverages his B.S. in Philosophy from Northeastern University to ask questions that get to the heart of business issues, while his MBA in Marketing from the Thunderbird School of Global Management at ASU translates management philosophy into real strategic growth.

Insights to fuel your marketing business

Sign up to get industry insights, trends, and more in your inbox.

Contact Us

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.

Latest Posts